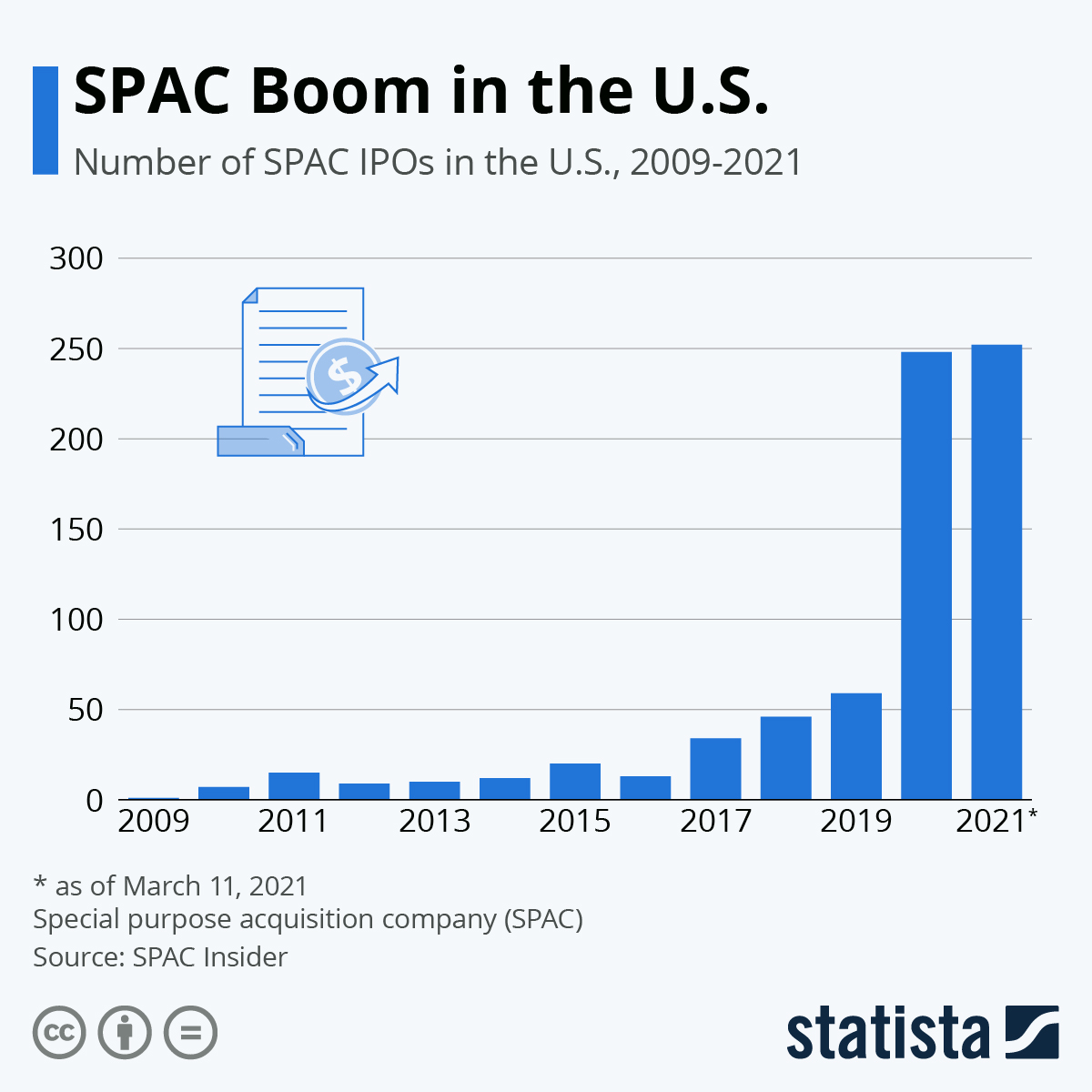

SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies – aka “blank check companies”) are the new new new thing, but they really aren’t. Blank check companies have been around for some time, and in the past, there were more failures than successes.

Now, everything has changed and everyone wants to do things with SPACs. There are powerful benefits – a fast path to an IPO without a lot of the hassle and a path to liquidity.

However, a fair number of executives and investors aren’t entirely clear on the process, so I thought I’d jot down some notes as to what a SPAC is and how the process operates — at least at a high-level.

Here’s how a SPAC works (using approximates):

- A group of well-connected execs (the sponsor) partner with an investment bank to do an IPO.

- The sponsor doesn’t receive any cash compensation, apart from expenses. However, in exchange for suffering for up to two years without any salary, they get to purchase 20% of the SPAC as “founders shares” for a nominal amount of money. (The economics are ridiculously in favor of the sponsor but it’s Wall Street, so whatever.)

- The sponsor will also buy warrants to fund the SPAC’s operations (warrants are similar to options1). This is done by buying several million warrants at $1.50 each to purchase the stock at $11.50.

- Proceeds from the IPO are put into a trust. A relatively small amount of money from the IPO will be be put aside to fund expenses.

- The sponsor usually has 18-24 months to find a target company to buy. Once they agree to buy a company, there is a process of getting approval from the shareholders. Shareholders who don’t like the deal can get their shares redeemed from the trust. (yep, one of the few places in Wall Street where there is a “money back guarantee”).

- If a SPAC doesn’t find a company to buy, they also have to give the money back from the trust.

- The shares offered in a SPAC IPO are not typical – they are hybrid securities, called “units”, each unit being a share with a warrant component. The stock is almost always priced at $10 (it’s a nice, easy number). And the warrants typically exercise at $11.50.

- The ratio of warrants per share is referred to as warrant coverage, an investment term which means how many warrants are offered as a percentage of a share offering. Less warrant coverage means less dilution for the target company. Units typically have 1/2 or a 1/3 of a warrant for every share. This is why when you look up a SPAC on an exchange, it might look odd, in that there will also be a warrant portion.

- To make it clear, let’s say you have 10 units, each with 1/2 a warrant. You would have 10 shares and 5 warrants (warrants are never exercisable partially, they are only exercisable in full).

- The stock becomes free-trading and may go up in value2.

After the SPAC finds a target company, the real work starts.

- The SPAC will offer a price to the acquiring company – usually a competitive price. It’s a sellers market and SPACs are anxious to get deals done. So they pay well. However, they usually pay largely in stock and hence, if the target company performs poorly, it will not go well for everyone.

- The SPAC will solicit shareholder approval for the SPAC. This will be done through a proxy statement (the form used when soliciting shareholder votes). If the company is also registering new securities, it would use a Form S4 (which combines a proxy statement with a registration of the new securities). This is useful to know as you find out a lot in a proxy statement, such as exec comp, business relationships, outlook, etc. in a relatively simple and clear format.

- This shareholder approval is like a mini-roadshow. At this point, the target company and the SPAC will do price discovery to see if the deal is marketable. If investors yawn at the deal and it’s not appealing, the deal may get scrapped.

- In some cases, a SPAC will want to raise additional capital during the merger. This may be used to buy out existing shareholders of the target company, or to provide additional capital to the combined entity.

- The additional capital may be raised in the form of debt, but is often done in the form of a Private Investment in Public Equity (PIPE). PIPEs are common instruments on Wall Street for public companies raising money in a fast, efficient method. Investment funds are active in this area, so the buyers are there; and the paperwork and process is relatively straightforward.

- If the shareholders approve and all the paperwork is proper, the merger is done and the SPAC goes away and the target company becomes the new public entity.

Dilution

Dilution is an important consideration for the target company. Let’s look at some basic math. To keep things simple, I’ve kept fees and warrants out of the picture for now. The fees are important, but the warrants become very important. More later.

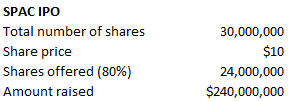

Let’s say we have a SPAC IPO (“Trifecta Spac”) with 30 million shares, offered at $10/share. 20% of the post-IPO shares are reserved for the sponsor. The IPO would look like this:

Oversimplified, the resultant cap table would look something like this:

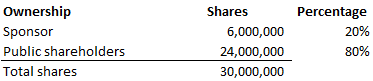

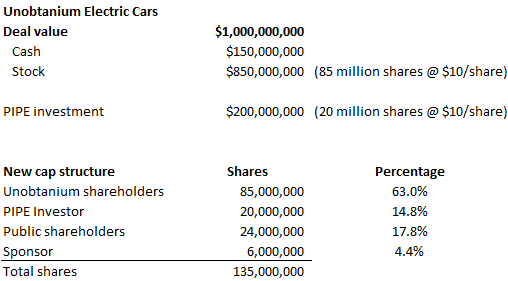

The sponsors find a company, “Unobtanium Electric Cars”. They offer $1 billion to acquire this company, payable partly in cash and partly in stock. Like a typical M&A deal, the $1 billion figure would be on a Total Enterprise Value/Debt Free Cash Free basis (simply, the price of the company without regard to debt and cash).

Now, the cash portion is tricky, because there is still a chance that shareholders might redeem, so they need to hold some aside for potential shareholder redemptions (in addition to the fact that the newly combined entity likely needs to have cash on the balance sheet).

So the sponsor offers $150 million in cash, and $850 million in stock:

The post-merger cap table would then look something like this.

However, there is a desire to raise additional capital at the time of the merger. The two entities raise $200 million through a PIPE, concurrent with the close of the merger. The price of the PIPE offering will be $10/share. In that case, the result looks something like the following:

Warrants

Warrants are a key part of a SPAC, in that they add extra return for the sponsors and the initial investors.

Warrants are usually exercisable at 15% above the initial IPO price, or $11.50 However, the SPAC will often limit the upside on warrants by forcing a redemption if the stock exceeds $18 (effectively capping the gains).

There are generally two warrants applicable to a SPAC deal:

- The Sponsor Warrants: The SPAC sponsor initially purchases warrants to fund the SPAC (and to generate more upside for the sponsor). These warrants are typically priced at $1.5 per warrant at an exercise price of $11.50. Most SPACs raise $7-$10 million by this method. Let’s assume Trifecta Megaspac raised $7.5 million at $1.50/warrant. This makes for 5 million shares exercisable at $11.50/share.

- The Unit Warrants: These are the warrants provided to the initial investors. Since most deals these days are being done at 33% warrant coverage (meaning, for 3 shares, there is 1 warrant), we can assume that Trifecta, with 24 million units, would have 8 million warrants available.

So, if your math is quick, we have 13 million shares as an overhang. These will be dilutive starting at $11.50/share. However, we should look at the whole picture (the Treasury Stock Method, which assumes that all the in-the-money warrants will be exercised) to really understand the fully dilutive picture.

So at $18 we would have a picture of something like the following:

That’s the big picture and again, my math does not include fees, and fees payable to the SPAC board, and some additional dilutive effects of warrants not covered here (and probably many other things). It’s illustrative.

If you are seriously considering a SPAC, get a good banker to represent you on the sell-side. And if you partner with a SPAC, remember that you’ll need to be every bit as good as a real public company. You’ll need the networks in place to market the new merged entity (which a good SPAC can help with), you’ll need to have your financial house in order and you’ll need to run like a real public company.

The SPAC offers major benefits over going public directly: The paperwork is relatively straightforward and you’ll have very clear picture as to what the market appetite for your company is before going through a full IPO process (speed to market is no different between an IPO and a SPAC). On the downside, you could do the deal at $10/share and find yourself being a crappy $2 stock in a year. So do your homework and get good help. It means a lot.

If I’ve made any errors, just email me or put something in the comments.

References:

https://www.pwc.com/us/en/services/audit-assurance/accounting-advisory/spac-merger.html

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4403134-what-is-spac-everything-spac-and-how-works-video

- 1 SPAC warrants are similar to options, with some exceptions, most importantly a) their availability may be triggered on certain events such as revenue or the strength of the company’s share price over time, and b) the money for the warrant exercise goes directly to the company’s treasury. [↩]

- However, any increase is speculative; the intrinsic value of the stock is the offering price (the $10). That’s what the “guarantee” is behind the stock. Anything excess is speculation. So if you find a SPAC trading at $15 and you’re excited about it, you only have the guarantee of the $10 held in trust [↩]

One reply on “Anatomy of a SPAC”

[…] a follow-up on an earlier post of mine about SPACs, I’m sharing some information from a recent deck by AGC, one of the leading SPAC […]