Each year, Mary Meeker of KPCB does a data-overwhelming presentation on the state of the internets. Her slides and slide volume are famous: this woman knows data (there are even attempts to make her slides better).

There are not many surprises in this year’s presentation, but there are important highlights that are valuable.

There’s a lot of money being made. Tell us something we didn’t know.

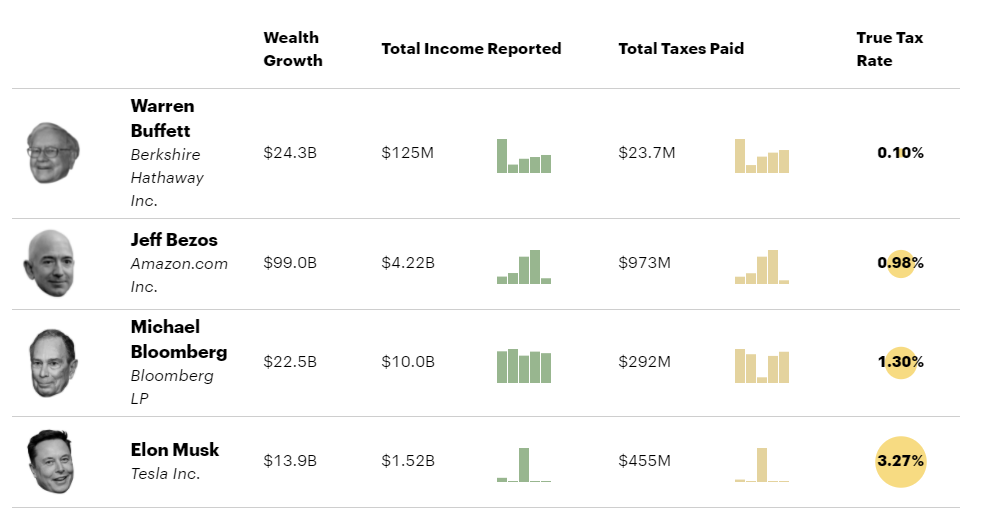

The presentation starts with a nice throwaway slide. It’s largely useless but a nice way for Kleiner Perkins to pat itself on the back and for Warren Buffet to feel silly.

(So the market cap of internet companies is massively bigger, because, well, the internet is massively bigger. Plus there’s this asset inflation thing going on.)

Okay, on to the meaty stuff…

If you haven’t figured it out, it is all about mobile.

Mobile, peeps! Just yesterday, I went to the website of a well-known technology company, only to find that the website was unusable on mobile (clearly, they ignored me).

But this is all not about creating mobile websites. It’s about mobile as the fundamental paradigm. The desktop is a “who cares” proposition. If this isn’t clear to everyone within hailing distance, I don’t know what else to say.

So, we start off with the obligatory OMG THERE ARE SO MANY MOBILE USERS!!112!!

Whatever.

But this is interesting:

In other words, the daily usage of digital media on mobile is now the majority of the time spent during the day. Kind of obvious, but it’s still yet another wake-up call.

But don’t worry, there’s still plenty of greenfield:

ARPU (not a typo)

Then, she talks about advertising, but in the context of Average Revenue Per User (ARPU), it’s up but the growth rate is slowing.

It’s still incredible, but…

Here’s the impossible-to-understand chart by Mary Meeker:

But someone (namely, me) puts the data into a spreadsheet and then it’s clearer what’s happening.

Okay, that looks sweet.

But now let’s graph the growth of Facebook:

And Twitter:

Yeah. The growth is slowing. Ugh.

Desktop advertising. A big fat “meh”.

Oh, and just in case you didn’t get the memo, desktop advertising isn’t where the party is.

TV is so… not

Now, again on that whole mobile thing, take a look at mobile screen viewing.

It’s beating TV.

(And she also basically says not to even bother with horizontal videos for ads, stick to vertical.)

Enterprise software is dead. Long live enterprise software.

There are quite a few slides spent on something that I really consider important.

Enterprise software as we have known it is dying.

Instead, we have innovative and (often) amazing tools by companies like Slack (reducing email traffic materially), payment gateways (Square and Stripe), business intelligence (Domo, my personal man crush on an enterprise software company), secure documents (Docusign), customer messaging (Intercom), customer service (Directly), HR (Zenefits), spreadsheets (Anaplan), recruiting (Greenhouse), and much more.

This is important and what I’m spending a lot of my time right now working on — the complete revolution in enterprise software, from stuff that was disintegrated and required proactive action on the part of the user, to products that are integrated and are themselves proactive (domo is a perfect example). Some of these solutions are truly awesome, and I mean that.

Big data was the first big breakthrough, but there’s a lot more behind the story. It brings the vision of software as a unifying activity, not what it has been in the past — by any stretch of the imagination.

Do I sound breathless? Yup, guilty.

So onward, soldiers, let’s look at some more slides and have a bit of fun.

Messaging is huge.

Okay, messaging is big. I mean — really big. Messaging apps are top in global usage and sessions. No surprise, since human beings spend a vast amount of their time communicating (even if it is cat videos and other crap).

Will mobile be the central communication hub? Of course. It’s already happening. And that’s really important to understand if you are into that space. Or any similar space, for that matter.

Power to the peeps.

Now, along the way, some people may have forgotten about the most critical aspect to this whole community thing: the actual user.

And the user is now the curator and creator of content. It’s really massive.

Look at this data: Power to the people, indeed.

And listen to the kids. They are leading the pack:

Cybersecurity wake-up call.

Then we move into my wheelhouse, security, where there are no surprises. But certainly some clarity. Again, mobile, BYOD, these are real issues.

The global stuff.

So then we get to a touchy subject, the global economy. If you’re pro-China, now is the time to pay attention. And if you’re pro-America, now is the time to really pay attention.

Now the good news: Americans will have more time to spend on cat videos on their smart phones.

And with US population growth outpacing job growth, more and more people are on the dole. There is probably a bit of bread and circus going on, but one cannot discount what has happened to the US.

Immigration is slightly up. And that’s good, not bad.

Immigration is up. I think this is very positive, as immigrants, despite some who scream otherwise, infuse our economy and culture with freshness and vitality.

(Wait, you think that with downward job growth, this is a problem? Actually, no. Immigrants boost economies.)

Life still sucks for wedding planners.

And another reason we need immigration: We are going to need fresh citizens, because a) Americans don’t marry much anymore and b) the average household size has plummeted.

Pay attention to the millennials. They are the biggest portion of our workforce now.

And now, with millennials being the biggest percentage in the workforce, expect the workplace to change.

Because they have different needs and wants than other types of employees:

Keep a spare lance around.

And freelancers (yay fiverr) are 34% of the workforce. Yup.

And that’s good news, because the economy is not going to help them.

Elance, Airbnb, Etsy, Thumbtack, Uber, Fiverr, etc. are all a big help to freelancers.

China is doing the Estonia thing.

Okay, in China you can use WeChat to interact with the government.

Hey — I want that here.

There’s more on China and India starting on page 150 and the rest is other useful information, particularly on UI design.

So that’s my color commentary for now. You can see the whole report, here.